Who would want to invest in a power rack and not use it for squats, presses, and other iron-heaving pastimes? Well, I’d venture to say a lot of people; most of them just don’t know it.

Generally, three groups of people fall into this category:

- The dude who somehow ended up with a rack, but isn’t exactly sure how or why it happened. Maybe a buddy was storing it in his garage, and two years later, still hasn’t picked it up. Maybe he has a compulsive shopping problem, and Dick’s ran a Black Friday deal that he just couldn’t resist. Or maybe, he originally had noble intentions–perhaps even used it a couple times–but never made it back under the bar.

- The habitual lifter who either, due to injury, budget restrictions, or boredom is looking for a way to vary her training with inexpensive, generally unloaded exercises using a piece of equipment she already has.

- Someone like myself who trains people from all walks, runs and crawls in life, and wants a piece of equipment that can handle both an offensive lineman performing a 600 lbs back squat, and a grandmother learning how to properly handle her own body weight for the first time.

If you fall into either of the categories above, keep reading for some new ways to take advantage of that steel animal cage in your garage.

Pull-ups

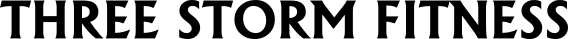

Let’s get this one out of the way early. Hopefully, it’s very obvious to you that the 1” bar mounted at the top of the power rack, designed for the express purpose of doing pull-ups, is a pull-up bar.

Facetiousness aside, a power rack pull-up bar has one distinct advantage, and that’s stability. A rack bar allows you to load up the movement with extra weight, or perform more dynamic variations of the exercise like kipping and muscle ups; neither of which I would dare attempt on the bar I haphazardly installed in my kids’ bathroom doorway.

With a gun to my head, I could probably rattle off 25 pull-up variations before I started to pee a little. That said, my two go-to straight bar variations are the classic pronated grip, and towel pull-ups; each of which probably have two dozen unique variants of their own.

If you’ve never seen anyone do a classic pull-up, let me be the first to welcome you to the Internet

Towel pull-ups offer the added benefit of extra grip development, and you don’t have to wipe the sweat from your palms before doing them. This is just one of several variations

If you can’t execute a proper pull-up, all is not lost. There are multiple variations to get you to greatness; band-assisted pull-ups are a fine choice, as are fixed arm hangs for time, and slow eccentrics (jump your chin over the bar, and slowly lower yourself down).

One of my personal favorite pull-up regressions, however, is the bench assisted pull-up, where you’re able to complete the movement in its entirety, while only pulling a portion of your bodyweight. Simply adjust your knee bend to vary the difficulty.

Even folks who can perform “real” pull-ups can include the bench variation (or any other assisted pull-up for that matter) into their workout. Next time you complete an AMRAP pull-up set, follow it immediately by an AMRAP drop set of bench-assisted pull-ups (you might want to shave your head first…combing your hair the next day might be out of the question).

Hanging

I’m not referring to hanging in the loitering sense, though you and your pals are certainly welcome to stand around your power rack with a case of beer and talk about lawncare. I’m talking about hanging to improve that wretched mess you call your shoulders and back.

Using the power of gravity is one of simplest ways to help regain your childhood shoulder mobility. Before I started hanging from the bar on a routine basis, I couldn’t reach my arms over my head without manipulating my back in an ugly way, but now look at me! Ok, you can’t see me, but I’m back to 180 degrees of full flexion without pain.

Also, for those of us with stressed out spines, dead hangs from the bar are an excellent exercise to decompress the vertebrae. I routinely hang from a bar after heavy squats and deadlifts to unpack my back. After a hundred pops and snaps, I often wonder why I subject myself to such spinal havoc…oh yeh, it’s because being strong is neat.

So how do you hang? Reach or jump up, grab the bar slightly inside shoulder-width, and relax everything but your hands. Allow gravity to shift everything into place. For an added stretch, actively try to push the bar toward the ceiling, or drive your feet into the floor (assuming you can’t touch it with your toes). I normally hold this position for 1-2 minutes. If my grip doesn’t want to cooperate, I just set the clock and pause it between breaks. Alternatively, If you have deadlifting straps, use them to tie yourself to the bar. Take some deep breaths and try to enjoy the process.

How could I talk about hanging from a pull-up bar with mentioning toe-to-bar hanging leg raises (HLRs)? Strict HLRs are one of the most effective (and consequently most demanding) anterior strength developers in the exercise ether. Classic HLRs require a bar high enough to keep your toes off the ground. Because I’m 6’4”, however, my Rogue R4 isn’t quite tall enough. No worries; dead stop HLRs are even harder, and nearly impossible to cheat, unless you jump…don’t jump.

Barbell Push-ups and Rows

Whether you’re progressing toward your first “real” push-up or training to total 2000 lbs at a powerlifting meet, you can no doubt benefit from adding upper body calisthenic movements like push-ups and rows to your program.

Modifying the intensity of either of these calisthenic classics isn’t rocket surgery (change the tempo, manipulate knee position, toggle between unilateral and bilateral hand placement; to name a few), however, my preferred method for both myself and my clients is centered around the power rack. Performing these movements on a rack-mounted barbell offers a couple unique characteristics.

First off, it’s one of the easiest ways to quantify progress. If the goal is to perform a push-up from the floor, the hand-elevated variation is an exercise you don’t want to ignore. In addition to logging set and rep completion, the hole numbers used during the exercise can also be tracked. This will give you the data you need to intelligently progress toward your goal.

Working with standard 2” hole spacing is completely fine, but a rack with Westside holes (1” spacing), like my Rogue R4, allows for very granular progression; think of it as adding 2.5 lbs plates to your bench as opposed to those of the 5 lbs persuasion.

I also prefer using the barbell, particularly for push-ups, because most people have an easier time activating their lats and shoulders while gripping the bar; generally more so than they do when their hands are on a flat surface. “Breaking the bar” provides the perfect cue for setting up a strong posterior foundation for horizontal pressing, especially when it comes time to bench.

Just as you can use the power rack to perform regressed variations of these definitive bodyweight exercises, you can leverage its versatility to add intensity as well.

Rather than placing your hands on the barbell, let your feet rest on it for inverted push-ups. To progress rows, place your feet up on a box or a bench (or, if you’re long enough, the pull-up bar at the opposite end of the rack).

Bonus 100 push-up drop set finisher

One of my favorite ways to finish an upper body push-centric workout is to bang out 100 push-ups as quickly as possible in the following fashion:

Begin with your feet high on the barbell, in the most inverted position you can manage. If you can do handstand push-ups, start there. Perform as many push-ups as you can, while keeping one or two left in the tank.

When you’ve hit your limit, drop down and quickly lower the barbell 2”. Get back up there once it’s in place, and repeat with as many reps as you can.

Continue this process until you either reach the floor, or hit 100 reps. If you reach the floor without hitting 100 reps (you are a total stud if you finish beforehand), turn around, place your hands on the barbell, and perform as many reps as you can in the hand-elevated position.

Keep raising the barbell 2” until you finish your 100 reps.

If you really want to add some fun, superset 100 pull-ups and rows (dictated by the height of the barbell) in between your push-up sets.

[activecampaign form=1]Barbell height isn’t the only way to vary the intensity of these movements. As noted earlier, the greatest advantage of your power rack is its stability; especially if it’s bolted to the floor. If you have some heavy resistance bands, you can perform loaded variations of these exercises that rival the potency of any Globo Gym machine.

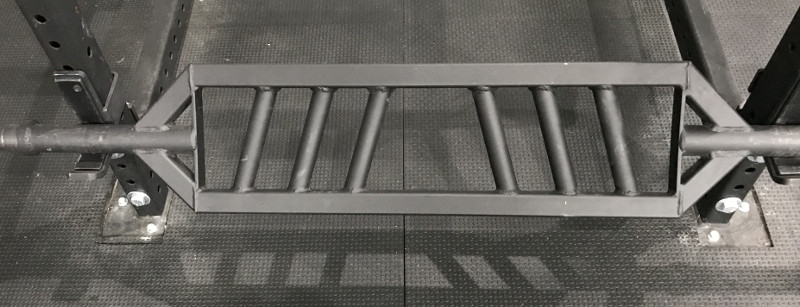

One of my favorite exercises for building up the back is heavy banded barbell rows. First, set your barbell to the appropriate row height; just below the nipple line (hehe…nipple) is a good place to start. Next, place another barbell on the ground at the opposite end of the rack. This will serve as an anchor for the band. Fasten a heavy band to the grounded barbell, and secure it around your waist. Now, grab the bar in front of you, and get to work.

Make sure the barbell on the floor is secure! The band pictured is loaded with almost 200 lbs of potential energy, which pretty much makes the bar a lethal weapon if it comes loose through the uprights

The same banded resistance can easily be applied to push-ups. Simply wrap the bands around your waist, grasp each end securely across your palms, assume the push-up position, and shimmy the bands across your upper back (I find this position offers the best distribution of resistance).

While you can absolutely perform banded-resisted push-ups from the floor, the bar, again, seems to carry over well to the bench press, especially when using the bands to excruciatingly draw out the eccentric phase.

Finally, what dissertation on push-up and row variations would be complete without a nod to suspension rigs (e.g., TRX or WOSS Training). Throwing an anchor strap over a power rack post lends an ideal suspension training environment. This non-invasive configuration doesn’t require you to drill holes in your ceiling, and the arrangement can be set up and torn down in seconds.

Bonus exercise:

If your power rack offers a strong safety bar assembly, two barbells can easily be placed in a parallette configuration. Before I got my Matador dip bar attachment, I routinely use this setup to perform dips.

One feature of barbell bodyweight exercises that I particularly enjoy is the amount of new variations that become available by way of specialty barbells. Take, for instance, the multi-grip angled Swiss bar. I train several clients with beat up shoulders, and the angled pronated Swiss allows nearly all of them to perform push-ups without any pain. For most folks, it takes the stress off of the shoulders, and puts it on the triceps and pecs.

I broke my wrists a couple times kickboxing in college (ok, I also blacked out and fell down a hill one crazy Halloween weekend…and a stairwell), so mobility, especially in the supinated position is a challenge. By performing supinated rows with the angled Swiss, I’m able to hit my biceps and lower lats a lot harder without sacrificing the health of my wrists (and upstream elbows and shoulders). Of course, you can also lay the bar on top of the rack for a huge variety of pull-up options.

You aren’t limited to Swiss bars. If you have other specialty bars in your gym, go ahead and get creative. So far I’ve tried:

- Dips and pull-ups in between a racked trap bar

- Push-ups on a Supra curl bar (similar to the Perfect Pushup device)

- Pull-ups and bodyweight tricep extensions with a front squat bar (murder on the grip)

- Pin squats with an SS Yoke bar underneath the safety pins (rack the bar directly below parallel with the pins an inch or two above the bar, and push against them for time). I wouldn’t recommend this one unless your power rack is bolted down.

More Fun with Bands, Tubes and Ropes

Not having access to a $5000 crossover cable machine sucks…unless you happen to have a power rack, and $30 worth of repurposed rubber bands and surgical tubing.

I used to scoff at idea of using bands. How could a piece of equipment hocked by Marie Osmond get me gains? I mean, yeh, she’s totally jacked, but c’mon! The truth is, by leveraging the stable anchor of a power rack, and making a small rubber investment, you can replicate nearly every commercial crossover exercise in your garage gym with a few resistance bands.

Trying to list every possible banded exercise in this post would be like me trying to list all my favorite Osmond songs; it would go on forever. I will, however, share a few of my favorites.

Crazy Horses, Let Me In, One Bad Apple, Goin’ Home…and now the exercises…

Bonus triphasic bicep killer:

Try this fun little sequence at the end of an arm workout to toast your biceps. I originally saw Jeff Cavaliere demonstrate this with a cable machine on his Athlean-X channel. While it’s great for the biceps, the same triphasic failure concept can be safely applied to nearly any isolated assistance exercise.

First, let’s focus on the concentric phase. Perform as many controlled high curls with your resistance tubes as possible. Upon failure, move to the eccentric phase.

Walk back into the top of the high curl position, and lower your arms slowly (4-6 seconds) to the bottom position. Complete as many reps as possible.

Finally, to achieve total triphasic failure, hold an isometric flex at the top of the high curl for as long as you possibly can (if you’re not shaking, you’re not working).

If that doesn’t fluff your falafel, I think I know what might. The power rack can also be used as an anchor to develop explosive power. Heavy banded sprints are a simple, but effective tool to keep in your rubber band belt. Perform them in short, quality low rep sets for power development, or HIIT intervals for an intense cardiorespiratory experience. Just make sure you perform a couple trial runs before getting too crazy. Without a stable base, the band will send you flying back into a steel post. That said, I like to this negative slingshot phenomenon into a positive, and call it “core-stabilizing deceleration training”.

An often overlooked power rack accessory is the battle rope. Sure, the posts make great anchors for rope slams, but that’s only half the fun. Rope pulls are a different animal entirely.

If you don’t have a climbing rope or a sled, you can still practice time pulling under tension with a thick battle rope and a rack. Simply loop the rope around a section of the rack and begin pulling hand-over-hand. Once you reach the end of the rope, switch to the short side, and repeat. Experiment pulling from different angles; midline from the safety bar, above from the pull-up bar, or below from the bottom rack.

You can add friction, and thus resistance, by looping the rope two or three times around the rack mount. Just keep in mind that the more loops you have, the more tangles you’ll potentially create. If possible, keep a spotter/knot untier on deck so you can work without interruption.

Mobility and Soft Tissue Work

Watch MobilityWOD, ROMWOD, or SmashweRX’s Youtube channels for an hour, and you know what piece of equipment you’ll probably see featured more than any other? The power rack. I already discussed the therapeutic benefits of hanging from a bar, but power racks offer oh-so-many more opportunities for the panacea known simply as “mobility work”.

The mobility exercises made easier with a power rack generally fall into two classifications; joint distraction and self-mysofascial release (SMR).

Joint distraction sounds terrible, but feels great. In short, you’re prying open and/or manipulating your joint complex–most often with a heavy band–in order to create more space for mobility.

Conversely, SMR sounds great (i.e., deep tissue massages), but usually feels terrible. It involves applying deep, targeted pressure on knots and adhesions in the muscles in order to hydrate the fascia (the connective webbing that keeps everything in place) and break up mobility restrictions. There are dozens of tools for the job, but an ordinary lacrosse ball is a good place to start.

For joint distraction, the power rack serves as a sturdy anchor. Nearly everyone who performs loaded squats–especially those with faulty movement patterns–has dealt with some bit of chaos in their hip sockets. I know that my femur has found itself in some strange neighborhoods over the years, and I like to think of my big black resistance band as the Uber driver that takes it home.

I’m not a doc or a physical therapist, but here’s the system that has worked for me:

First, I loop the band around the base of a rack post, and shimmy the other end as high on my leg as it will go (mind the stepchildren). From this position, I grip my fingertips to the ground or grasp a sturdy object, and crawl myself into whatever position I need to get into (again, I have 180 lbs pulling me in the other direction) in order to pull or push the hip joint back home.

Again, I’m no physio (get a second opinion before you try any of this), but here’s how I decide which direction to drive:

If I have pain during flexion (e.g., the bottom of an A2G front squat), I know that my femur is probably creeping anteriorly, so I use the band to drive it posteriorly. If I’m experiencing limitation or discomfort in the rear during extension (e.g., a deadlift lockout), I use the band to drive anteriorly (usually in a “couch stretch” position). I apply the same general principles to hip abduction and adduction as well.

Of course, I’m constantly trying to identify and correct the day-to-day behaviors that are causing my issues in the first place, but the method above has served me well as a band-aid while I figure things out (hope you enjoyed that pun).

My favorite part of this process is when I’m done, the band pulls me back up into a standing position like the “Smooth Criminal” anti-gravity lean

If your shoulders need some love, and hanging from a bar isn’t quite cutting it, try some banded shoulder distraction. Sling a heavy band over the pull-up bar, grab a hold of it and use the resistance to work the angles. I use this method primarily for shoulder flexion and external rotation (it also offers a mean lat stretch).

Did you by any chance notice the two red balls featured in the picture above? No, sicko, my hand is blocking those anyway…I’m talking about the two in the upper-righthand corner, stuck to the post. Those are Mag Mobility balls, and they’re currently my favorite power rack SMR tools.

If a rich man uses the Rogue Supernova Infinity/Monster attachment, and a poor man duct tapes a lacrosse ball to the bar, then I suppose a middle class man uses Mag Mobility balls. They’re basically lacrosse balls impregnated with a heavy magnet that sticks to the power rack (you can read all about them in my review here: Mag Mobility Magnetic Lacrosse Balls Review).

Regardless of which which weapon you choose, driving your traps, shoulders, lats, or whatever’s tight up against a rack-mounted mobility ball is almost sure to get the juices flowing again.

Finally, if you’re tight, desperate, and in a foreign land without your foam roller, look no further than the barbell for all of your smashing needs. I’m personally blessed with supple hamstrings, but for my clients who aren’t, their “favorite” medicine is what Dr. Kelly Starrett calls the “Monkey Bars of Death”.

Rack a barbell between knee and hip height, throw your leg over, placing your eager hamstrings on the bar, and apply pressure side-to-side. Continue applying these pressure waves while moving north and south on the bar. What a treat!

Wrap Up

Welp, I’ve finally realized my lifelong dream of writing a novel on power rack pastimes. Truthfully though, this story could easily be expanded into a trilogy…maybe even a prequel origin story! I only scratched the surface, and didn’t even touch on rack-mounted accessories like landmines, GHDs and specialty pull-up attachments. If I missed any of your favorites (and I’m sure I did), please share them in the comments below!

Visit the link below to sign up for a free 92 page issue of MASS Research Review (you can read my MASS review here) covering the following topics:

- Blood Flow Restriction Training Causes Type I Fiber Hypertrophy in Powerlifters

- Leave the Gym with a Little Left in the Tank

- Energy Availability in Strength and Power Athletes

- Hormonal Contraceptives Don’t Mitigate Strength Gains

- Power Training or Speed Work for Some, But Not All?

- The Role of Physical Activity in Appetite and Weight Control

- The Science of Muscle Memory

- VIDEO: Program Troubleshooting

- VIDEO Sustainable Motivation for Sport and Fitness